What follows is an informal, incomplete comparison between the experience of riding public transit in Los Angeles and that of a rider in Toronto and Montreal.

I offer the comparison because I can. I just returned from two weeks in Toronto and Montreal, and traveled exclusively by train and bus while there. Several transit buffs were kind enough to meet with me in these cities, and answer questions.

It might be more reasonable to compare transit in Los Angeles and San Francisco, as both are major cities in the same state and the same country. Unfortunately, I wasn't paying close attention the last time I rode the BART under Market Street. In Canada, I was.

I gave up my car here in 2001 and have done almost all my getting around since then aboard Los Angeles trains and buses. I ride the subway, a lot, the Blue Line, the Gold Line, the 18, the 20, the 16, a score of other bus lines, and any bus or train I need to ride while chaperoning trips for TransitPeople. I generally stick to my TransitPeople niche and write about transit only when a bus route we use is on the chopping block, but that doesn't stop me from following transit issues in the SoCaTa newsletter, and on la.streetsblog, and in the few transit-related articles to be found in the mainstream press.

In all of these past ten years, my focus has been entirely on Los Angeles. My world begins with the San Pedro leg of the 550 to the south and, as I'm not really a Valley guy, ends with the Orange Line to the north. I haven't taken a long step back and looked at transit elsewhere in the world.

This February, I did. I hope other Los Angeles straphangers are interested in what I discovered. I wish I had taken the look long ago.

Expect this post to be editted edited, Wikipedia-style, if readers write to offer clarifications or correct mistakes.

* * * * *

Los Angeles is a famously spread out place, unconstrained by the geographical factors that have limited development elsewhere. The city measures 469 square miles; the county includes the city of Los Angeles and eighty-seven separate cities more, in a whopping 4,084 square miles of total land area. Most of the county's transit services are provided by the humble motor bus. The MTA bus fleet hosts about 1,100,000 weekday boardings, versus 300,000 for the entire MTA rail system.

|

| Musician at Montreal's Berri-UQAM station |

Most Angelenos travel by car. According to SCAG's 2006 'State of the Commute' report, 75% of county commuters drove solo; only 11% rode public transit.

Toronto sprawls at its outskirts, but not at its center. (Ed Drass referred to his city as Vienna surrounded by Phoenix.) The city covers 243 square miles; the greater Toronto area -- including the Phoenix part -- covers 2,751, or 67% of the area of Los Angeles County. The Toronto Transit Commission (aka TTC), which serves Toronto proper, operates the third most heavily-used transit system in North America, behind only New York City and Mexico City. Average weekday ridership is about two and a half million ... or, nearly eighty percent greater than weekday ridership on Los Angeles' MTA, despite Toronto's smaller area.

More Torontonians use public transit to get around. According to the Appleton Foundation's GreenApple report, 28% in the Greater Toronto Area (remember, that includes the Phoenix part) bike, walk or use transit to get to work. Toronto transit expert Steve Munro said that transit's market share in the central city -- south of Dundas, in this case -- is as high as 70%.

Montreal covers 141 square miles; the greater Montreal area, 1,683. Average weekday ridership on the STM is just north of two million ... or, once again, considerably greater than that of the Los Angeles MTA, despite Montreal's smaller size. The GreenApple report notes that 29% in greater Montreal -- including, remember, the spread-out 'burbs -- bike, walk or ride transit to get to work.

Population density is lower in the city of L.A. than in the cities of Toronto and Montreal, but not that much lower: 8,169 per square mile, versus 10,288 per square mile in Toronto and 11,205 per square mile in Montreal.

Sadly, Los Angeles is a poorer place than either city. Per capita income here is about $27,000, versus $38,508 in Toronto and $35,343 in Montreal. This leads to an interesting takeaway: Los Angeles auto-based infrastructure almost forces residents to pay for personal automobiles, even though they are poorer than counterparts in Toronto and Montreal, who can reasonably expect to get around without them.

On to the observations:

Riders from all walks of life patronize trains and buses in Toronto and Montreal ...

* * * * *

On to the observations:

Riders from all walks of life patronize trains and buses in Toronto and Montreal ...

Los Angeles grew up around the car. I wish it hadn't, but it did, and most adults who can afford to buy cars to get around. What's left is a transit system that disproportionately serves the poor.

There are exceptions. Plenty of ritzy business suits can be seen on the subway bound to and from Los Angeles' Union Station in the commuting hours. And I regularly spot bookish-looking and stylishly dressed young urbanites on some city bus lines -- the 720 especially (particularly the 720 near Santa Monica or LACMA), but also the 217 and other buses that serve Hollywood -- who strike me as "riders of choice," to borrow the phrase that Ed Drass and Steve Munro used of some riders in Toronto.

I don't know that they are, of course. I don't tap on their shoulders and ask probing questions about their finances. I am guessing.

|

| Ed Drass at Carlton and Yonge in Toronto |

Toronto and Montreal are entirely different. The subway networks are large, and trains run often; in Montreal, rush hour headways can be under three minutes. The fantastically wealthy may insist on their cabs and limousines, but everyone else seems to ride the TTC or STM, or, at least, looks like he could. The websites of many central Toronto businesses provide transit directions.

Whatever the stats: I detected no appreciable difference between what I saw on the sidewalks and what I saw on trains and buses in either city. The atmosphere on some Toronto subway cars struck me as faintly formal, more like what one would expect in the seats around a departure gate at JFK than on a public transit train. Some self-conscious riders might even dress up a bit, before riding the subway.

... but politicians won't.

I regularly run into fellow Los Angeles transitophiles -- or transit geeks, or transit advocates, or whatever you want to call us -- on buses and trains here. Dana Gabbard. Kymberleigh Richards. Many from SoCaTa, several from the BRU. Joe Linton. Lois Arkin, of EcoVillage. John Walsh. Perias Pillay and Denisse Castillo of TransitPeople, a little volunteer organization with which I am more than glancingly familiar. I also have run into MTA staff, at least on the subway, including former CEO Roger Snoble.

In ten years of more-or-less daily bus and train trips, I have run into one MTA board member. Just one: Allison Yoh, long ago anointed by former mayor James Hahn because someone thought it only decent that a genuine transit rider should have a board seat. I met Ms. Yoh in the back rows of an eastbound 720 as I struggled to find seats for a class of grade schoolers.

That was the last time I saw an MTA board member on a bus or train, at least not when a camera wasn't present. The mayor's hypocrisy in this regard was so great that reporter Duke Helfand called him on it, in an 11/14/06 article in the Los Angeles Times. The mayor encouraged transit use for everyone else, but rarely or never rode it himself, even though he lives a block from a Rapid Bus stop. According to Helfand, he did his commuting in a police-chauffeured GMC Yukon.

Dana, Kymberleigh, Joe, Lois, John: I offer a bittersweet consolation. Canadian politicians don't seem to be any different. The Montreal STM did set aside a board seat for a transit rider, but this did not inhibit Mayor Tremblay from simply ignoring the figurative reservation card, and naming politician Michel Labrecque to the seat instead. Steve Faguy wrote about this at length on his blog, but with such colorful language that I am squeamish about linking to the article here. (I do, after all, direct a children's organization.)

|

| Steve Faguy at Montreal's Berri-UQAM station |

In Toronto, Steve Munro, Rob Mackenzie and James Bow could offer no names of politicians espied in casual, just-like-the-rest-of-us rides aboard the TTC. Ed Drass supplied one: Councillor Denzil Minnan-Wong, glimpsed on the subway on at least one occasion when no cameras were present. But only that one.

"You might want to be careful [about making an issue of this]," Ed counseled me solicitously, as he knew I had a meeting at City Hall. "This might be a sore subject for them."

Canadian and American politicians alike cultivate transit development where it will be politically beneficial, and not necessarily where it's needed.

In Los Angeles, the MTA has cut or proposed cuts for express buses on Florence and Western, while approving a light rail line that will serve Crenshaw Boulevard. I have logged many hours on the Florence 711, and perhaps fifty trips in the past ten years on the Western 757. The buses always have been crowded. One teacher wondered aloud in an e-mail to me how MTA could even dream of eliminating the 711.

In contrast, transit on Crenshaw is now so light that MTA is able to serve the corridor with the every twenty minutes 210, and the every half hour 710. A light rail line is hardly needed on Crenshaw, but Crenshaw is going to get one.

|

| Sheppard subway car at Don Mills station in Toronto |

My impression from conversations with Ed Drass, Steve Munro, James Bow and Steve Faguy is that Canadian politicians also steer transit development to where it will be politically beneficial. The TTC's one billion dollar Sheppard subway may exist entirely because of the efforts of former mayor Mel Lastman, who wanted his North York stomping grounds to have a subway line, whether it warranted one or not.

In Montreal, Steve Faguy described political jousting between three territorial factions: the Anglophone west, which votes for the liberal party, the Francophone east, which votes for the separatist party, and the suburbs, which are up for grabs. Politicians carefully court the fickle suburbanites, and may offer them a new STM line, even if they don't particularly need one.

In Montreal, Steve Faguy described political jousting between three territorial factions: the Anglophone west, which votes for the liberal party, the Francophone east, which votes for the separatist party, and the suburbs, which are up for grabs. Politicians carefully court the fickle suburbanites, and may offer them a new STM line, even if they don't particularly need one.

The STM now contemplates three new subway lines: one for the south shore, one for the north, and one for Montreal. The need may be far greater in Montreal, but that's not how planning decisions are made.

Toronto has a farebox recovery ratio of over 70%.

"Farebox recovery ratio" refers to the percentage of expenses recouped from the farebox. If the Greater Barstow Transit Authority receives $600 from fares but needs $1,000 to do its business, then the farebox recovery ratio is sixty percent, and the agency is dependent on government revenue (or taxpayers) for the remaining 40%.

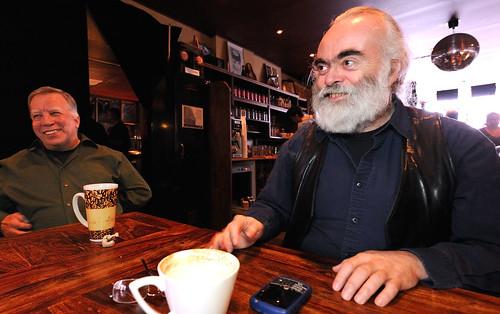

|

| Rob Mackenzie, left, and Steve Munro in Toronto |

In Los Angeles, the farebox recovery ratio is under 30%. I could have looked up Canadian statistics before I traveled ... but I didn't, and so blinked and pushed my chair back in surprise when Steve Munro and James Bow gave me some figures for Toronto: consistently over 70% for the TTC, and a whopping 88% for the Toronto GO Transit commuter rail network.

(According to the TTC annual report, the farebox recovery ratio dipped to 66% in 2009, but was 73%+ in 2008 and 2007.)

Steve Munro noted that the heavy off-peak hour ridership helps make the TTC's numbers as impressive as they are. Rail and streetcar lines are loaded with passengers before and after rush hour; those passengers pay their fares, and the nickels and dimes -- or loonies, as Canadian dollars are called -- add up. He also noted that the TTC gets about 10% of its revenue from advertising, in-station kiosks and other revenue enhancers. Stations in both Toronto and Montreal offer much, much more advertising than is the norm in rail stations in Los Angeles.

The Montreal STM's farebox recovery ratio is lower than Toronto's, but still an impressive (by U.S. standards) 57%.

"But look at how much more they charge for a pass!" Los Angeles daily, weekly and monthly passes go for $6, $20 and $75 dollars, respectively. The STM charges $8 for a one day pass, $22 for a weekly pass and a bit less than Los Angeles, $72.75, for a monthly card. The TTC (with the highest farebox recovery rate) charges much more: $10 for a day pass, $36 for a weekly pass and $111 for a one month pass.

This is true, but a monthly pass in Toronto and Montreal provide a lot more mobility than does a pass in Los Angeles.

|

| In-station kiosk in Toronto |

I'll refer to another city, as more Angelenos know it: New York. A thirty-day New York City transit metrocard goes for $104 -- about 40% more than a Los Angeles pass -- and provides unlimited rides on New York City subways and local buses. Can you imagine anyone suggesting with a straight face that the New York City metrocard does not provide forty percent more mobility than the equivalent in Los Angeles?

Canadian politicians also make expensive mistakes.

The comparison between Toronto and Los Angeles government left this American feeling very much 'less than' ... and so I was quietly relieved to learn of the Scarborough RT, a blunder at least the equal of any on my home turf.

Apparently, it was a well-intended blunder. Former Ontario premier Bill Davis intended the RT as a technology showcase. Instead it became a technological orphan, and also devoured funds that could have been used elsewhere for a streetcar network. Today Scarborough-bound TTC riders must get off a subway at the Kennedy station and ascend several levels to board an entirely different train to continue in the same direction.

The terrific farebox recovery ratio may indicate that GO Transit is well run, but, according to Steve Munro, this has not inhibited its leaders from serious discussion of offering five to ten minute all day headways on its network of commuter trains. This would make for a simply tremendous commuter rail network ... but, according to Munro and Bow, few at GO seem to want to address some essential nuts-and-bolts details of this plan, such as how people will get to the frequent-running trains, and where drivers will park.

|

| Scarborough RT at Kennedy station |

Torontonians complain about their transit system.

If I spoke French, I probably would have overheard bellyaching about the STM in Montreal. The transit systems in both cities struck me as nearly paradisiacal, after my years in car-centric Los Angeles, but we homo sapiens seem to be genetically disposed to notice the bad more often than the good. Maybe other species are, too; we just don't understand mutts when they grumble about another dinner of dry dog food.

I have heard Angelenos complain of enduring savage winter mornings, in which temperatures dropped heartlessly to 50 Fahrenheit. This must sound as unreasonable to a Canadian as complaints about the TTC and STM sound to me.

Toronto and Montreal include huge, underground shopping centers adjacent to rail stations.

Picture a large Los Angeles mall. The Westside Pavilion is ideal, but Fox Hills Mall or the Beverly Center will do.

Now, imagine this mall entirely underground. All levels of it.

At one end of the mall, imagine a tunnel leading to turnstiles and stairs to a subway platform. Picture yourself approaching these turnstiles, and looking to one side. Before you are electric doors leading into another enormous underground mall, also adjacent to the subway entrance, and the equal in size of the one you just left behind.

Visualization complete? Now imagine malls flanking the next subway station south, and the one after that, and a series of underground walkways connecting the whole smorgasbord together. An underground city.

The map of Toronto's underground PATH network is here; the Montreal map is here. The maps hardly do justice to the developments' scale. Ed Drass told me that I could walk -- walk! -- underground from the Dundas station to Toronto's Union Station. I had to try it for myself; Ed was right.

A drawback: you will readily find high margin retailers like Abercrombie & Fitch and Victoria's Secret in these underground cities, but fewer blue collar offerings like McDonalds, and nothing at all like Sam's Club or Food 4 Less. Underground metropolises can't be cheap to build. My guess is that rents are prohibitively expensive. Googling for 'Costco' near Toronto found several locations -- but all in the spread-out, car-oriented 'Phoenix' part, and not in the transit-centric 'Vienna' center.

The Toronto TTC has almost no graffiti.

I am so accustomed to being surrounded by graffiti on Los Angeles transit lines that I felt strangely uncomfortable to ride a train without it. I guessed that something was off, didn't know what it was, and finally diagnosed the root of my unsettled state after an hour on the Toronto subway.

|

| Interior of a Toronto TTC car |

No tagging. Or virtually none. I finally spotted the first instance of "scratch-iti," as Ed Drass puts it, late in my first day on the Yonge-University-Spadina line, and another instance of it on the second day ... this after spending nearly all of both days on one transit vehicle or another, as befits a visiting transit geek. Later, when I rode the Bloor line, I discovered considerably more tagging -- why on that line, I couldn't say -- but still far less than on Los Angeles' Metro.

According to Steve Munro, tagging on the TTC was much more prevalent three years ago. The agency rolled up its sleeves, figuratively speaking, and tackled the problem ... successfully, according to this visitor's impressions.

I did see plenty of tagging in Montreal, although not as much as on lines in Los Angeles.

There are almost no homeless in Toronto, and no ghetto.

I spotted one man, just one, asleep next to an indoors stairwell near City Hall. I did spot several I would describe as psychologically troubled, but their dress and manner suggested that their essential needs for food, clothing and shelter were still being taken care of. I did not spot anyone who looked close to homeless riding Toronto trains or buses, or in a Toronto train station.

As for the ghetto: the closest Toronto seems to come is Regent Park. I might have walked the wrong streets (or the right ones), but my hour there left me with the impression of a rough, apples-to-oranges equivalency with the Washington-near-Arlington neighborhood in Los Angeles. I caught myself double-checking street signs to convince myself that I was in a neighborhood that anyone had described as ghetto-like.

|

| James Bow, left, and Rob Mackenzie in Toronto |

It should be mentioned here that Toronto is a city famous for good government, that has gone by such enviable nicknames as "Toronto the good" and "the city that works." Their citizens may elect leaders who occasionally manage to fix problems, rather than trot out lugubrious quotes about them.

Montreal, I'm afraid, does not share this reputation for good government. (You can see this article to learn more, although Steve Faguy said that some in Montreal regard the article as too harsh.) I quickly spotted plenty of homeless in Montreal. (Not that good government and the absence of homelessness are inextricably joined at the hip.) I didn't stay long enough to investigate its ghetto, if there is one.

The under-the-105 Green Line stations excepted, Los Angeles train stations are more attractive than train stations in Toronto and Montreal.

MTA may offer larger allowances for station artwork, or may simply spend the funds more wisely. The next time you await the Red Line at the Santa Monica station or the Blue Line at the Compton station, contemplate the plight of your counterpart in the snowbound north, awaiting the subway on the Bloor or Montmorency or Sheppard or Angrignon line.

The artwork at your station is more attractive. Score one for L.A.

The thorough Metrobits web site includes art from both Los Angeles and Montreal in a guide to the world's most beautiful subway systems. They give Montreal two stars, and Los Angeles one. They are entitled to their opinion, but I just returned from Montreal and have spent a significant hunk of my life riding the rails in Los Angeles. I stand by my view.

Los Angeles rail platforms are between north-south and east-west bound trains.

Walk onto the platform at Wilshire-Normandie or Florence or at Hollywood-Vine and you can travel in one direction or the opposite way, just by stepping to the platform's other side. Only the architecture at Wilshire-Vermont forces riders to choose between directions before descending to platform level. That makes for a much easier system for newcomers to navigate.

Not so in other cities, and not so in Toronto and Montreal. If you choose the wrong stairs to platform level, you will gaze helplessly across two sets of train tracks to the platform you had intended to stand on, and will have to go back up the stairs to repair the mistake. Effortful and confusing for tourists ... and, for all practical purposes, unfixable. Score another one for Los Angeles.

Streetcars have tourist appeal.

Or I think they do. I offer no evidence to support this view, aside from my undocumented impressions of riders' tastes gathered from my years of leading trips for TransitPeople.

I don't think the streetcars in Toronto can do much that buses can't. But they are colorful, quaint, picturesque, and appealing to tourists. Tourists bring money from out-of-town and spend it in town. The money stays after they leave. (Or can, if no one squanders it first.) Politicians and business people tend to appreciate the essential math at work here. The tastes of tourists deserve attending to.

A few Los Angeles children have ooh'd and aah'd over the colossality of some articulated rapid buses. Other than that, I have never heard anyone other than a hardcore transit geek express any interest in boarding a public transit bus for any reason.

A few takeaways:

• I will expect less from Los Angeles.

I think auto lobbyists can argue credibly that a traveler is richer with a personal automobile than with almost any form of transit. The car goes when you want it to go, where you want it to, protects you from the elements and from foul-smelling or foul-behaving passengers. You decorate its interior as you please, and share its space with whom you choose, or not at all. If the personal automobile didn't offer plenty of appeal, South Bostonians wouldn't joust for parking spaces and Singapore drivers wouldn't pay fantastic sums for a car permit.

But I think a community as a whole, particularly a big community, is far wealthier with a transit infrastructure. More ominously, the community that grows up without the transit infrastructure may never develop it after car-oriented development is in place.

Take a plane ride above Los Angeles and look at the freeway grid. Consider the almost uncountable billions already invested in those freeway lanes, and in the sprawling suburbs and auto-oriented malls those lanes serve.

Los Angeles can build a kind of city-within-a-city -- a meager city, perhaps, but a city nonetheless -- that relies on transit. (This is entirely ignoring the risk of earthquakes here, and setting aside the question of whether any new development should be pursued in a region so susceptible to devastation by the long-feared Big One.) I look forward to riding the Expo Line to the Natural History Museum, would love to someday step off a subway in Santa Monica.

But that city is never going to offer the mobility of the personal car, which can zip merrily around on that huge freeway grid just by being fed more gas.

The damage has been done. Many books are available that tell how it was done: Scott Bottles' Los Angeles and the Automobile, which describes long-ago decisions here to steer future development around the car, as Angelenos rebelled against inadequacies of the transit system; Internal Combustion and Getting There, which chronicle the General Motors-led conspiracy that ripped up our streetcar lines; and Reluctant Metropolis, which tells how city power brokers stonewalled planner Calvin Hamilton's blueprint for transit-centric development here in the 1970s.

I think the periphery of Toronto could go the way of Los Angeles, if it wishes, but can't imagine that Los Angeles can go the way of Toronto. An auto infrastructure may be forever. Toronto and Montreal should feel more grateful than they know that their transit networks are already in place.

• Reluctantly, I will stop expecting politicians to ride buses and trains. If politicians won't get out of their cabs, limos and SUVs in Toronto, a city famous for good government, I can hardly expect better in a city as notorious for bad government as L.A.

|

| Richmond Hill GO Transit line |

• If politicians can give up gerrymandering, they also could sign legislation to put approval of transit projects in the hands of technocrats who will build transit where it belongs, and not where it is politically expedient. That hope might show how little I know about politics. If so, I may be hard pressed to support future transit measures here. If the realities of political life force legislators to mis-allocate funds, then what argument can I offer to give them more?

I also must wonder aloud about some proposals to charge more for Los Angeles parking, as eminently sensible as those charges may be from an urban planner's point of view. (I am the proud owner of Donald Shoup's High Cost of Free Parking, and suggest you consider becoming one, too.) Our city's infrastructure is set, and the infrastructure almost requires car travel. A billionaire might not care if a parking spot goes for $5 instead of $1, but gardeners, construction workers, and moms-with-two-jobs do.

Of course, our government officials will offer oleaginous promises that every extra penny from the parking meter will be lovingly shepherded into cost effective, we'd-never-waste-a-dime-of-a-constituent's-dollar projects to expand transit services, so the no-longer-affordable parking space won't be missed.

Well, lo dudo. First, Los Angeles simply can't give that mom-with-two-jobs the mobility of a Toronto or Montreal transit rider. And second, all my years of armchair politico-watching here suggest that funds will be misused once politicians have a lock on them.

• I think Toronto could expend just a bit more effort to make the TTC graffiti and perhaps even litter free, and then brag lustily to the world of its cleanliness. I was quite impressed. I think others would be.

• Montreal is a much nicer tourist destination than I had supposed. (Okay, that's not relevant to this article. I just had to work it in.) Further, Montreal just might be poised to move to the vanguard of transit-oriented development. According to Steve Faguy, no one in power there supports expansion that favors the car. Whatever happens in Montreal's future is likely to be transit friendly.

(Steve Faguy also offered a favorable impression of Michel Labrecque as STM chair, even if Labrecque doesn't belong in the board seat reserved for transit users.)

• Years ago, I rolled my eyes at news of a suggestion by Mayor Villaraigosa that more advertising come to MTA. I now feel that the mayor had a point. We don't plan to make our own currency here out of eucalyptus shavings. Money matters. The ads don't have to be for liquor or casinos.

As for in-station kiosks: I presume that there are experts on these matters who count passers-by per hour, and can relate the number of passers-by per hour with the potential profitability of an in-station kiosk. Many Los Angeles rail stations may not be busy enough often enough to justify one. But some certainly are. It would be a humbling but valuable exercise to calculate how much money could have been earned from a kiosk in an appropriate location, and how much revenue has been lost from not having it there in years past.

* * * * *

In concluding, please let me thank all the transit buffs who met with me during my travels up north:

- Gentlemanly Toronto Metro contributor Ed Drass. Ed was especially helpful from the start, and offered some of the best quotes of my trip north of the border. (I haven't been able to work in the line that Toronto is like New York run by the Swiss until now ... but Ed, I did get it in at long last, as you can see.)

- Rob Mackenzie and James Bow of Transit Toronto. Rob provides regular news updates for this invaluable web site, and was kind enough to set up my meeting with James Bow and Steve Munro at Toronto's Only Cafe (only a block from a subway station, like so many things in Toronto).

- the obviously expert long-term TTC observer Steve Munro of stevemunro.ca, who joined us at the Only Cafe.

- Steve Faguy of Montreal, who blogs at blog.fagstein.com, and was kind enough to meet with me on short notice at the Berri-UQAM station. Steve works at the Montreal Gazette. I think he deserves a forum there for his transit writing, but I guess that's for the Gazette to judge.

- And lastly, I must offer one more thank you, to Toronto Councillor and TTC Chair Karen Stintz. I posed no transit related questions to her and spoke to her only of TransitPeople, but was still impressed by her courtesy and professionalism in meeting with an out-of-towner at City Hall.

(For more photos from up north, please see this Flickr link, for shots from Toronto, and this one, for shots from Montreal.)

* * * * *

Finally, as this document will be read miles from Los Angeles: please don't let the problems of our government reflect on the character of our people.

I have led hundreds of TransitPeople field trips all over Los Angeles, in South Los Angeles, the Pico-Union and other areas that tourists are warned to stay away from. Maybe those warnings to tourists should stand, but I have met wonderful, wonderful people in these places: bus drivers who go out of their way to accommodate our groups, passengers who beam at the kids as they stand to offer their seats. I have worked with scores of teachers and volunteers as dedicated as any to be found anywhere on earth. We Angelenos may not have made representative democracy work very well, but many of us are fine folks otherwise, if I say so myself.

-- first posted February, 2011